Synthesis Adoption Series: What Does the Rise of “Artificial” Ice Teach Us About the Future Adoption of Alternative Proteins?

• Market Update • Opinion • Feature

“History Doesn't Repeat Itself, but It Often Rhymes” – attributed to Mark Twain.

Of all the tales of disruption in history, in our view, the one with the most similarities to the coming disruption to the food system is the one about the disruption of ice.

The natural ice trade

The story can’t really begin until we set the stage to over two hundred years ago at the beginning of the 19th century. Jefferson had just been elected as the third U.S. President and through the Louisiana Purchase had doubled the size of the country. Alexander Hamilton had just been killed by Aaron Burr in the duel made famous today on Broadway. The Industrial Revolution had transformed all sorts of industries, from agriculture and food, to energy and building materials powered by steam, coal and iron. But day-to-day life remained hard, revolving around daylight hours, with most people having no electricity, running water, or central heating. Entrepreneurs and inventors were being rewarded by tackling these challenges.

In Boston, a man called Frederic Tudor embraced this entrepreneurial spirit. He had what seemed like a pretty crazy dream at the time – to export natural ice cut from the lakes and ponds of North America to the Caribbean. Growing up in Boston, he was used to the yearly ice harvest and having access to the cold to store food. But, in the early 1800s, to the residents of a tropical island, the idea of frozen water would have been as obscure as a mobile phone.

Not withstanding the unknowns around demand, the practicalities of supply were non-existent at the time. There was no existing ice export industry, he was starting from scratch and needed to learn how he could harvest, insulate, transport and store a commodity that melted. His first attempts left him bankrupt. But he persisted, and by the 1830s he had almost single-handedly created a flourishing ice export industry out of Boston, and ice, harvested from the lakes of North America, was one of the US’s most valuable exports. All this led to Frederic Tudor becoming known as the “Boston Ice King”.

Getting to this point was no mean feat. He had figured out all the key pieces of the ice trade puzzle. How to harvest, insulate store and transport ice – often improving these processes as he went. The Tudor Ice company saw huge growth in the trade of ice, and soon they were not the only ones as new companies popped up through the North-East. By the 1820s, there were packed ice houses all over the American South. The ice was transported not only to the Caribbean (in Havana they were particularly partial to ice cream) but as far as Rio de Janeiro and Bombay.

Demand for ice continued to grow as consumers became accustomed to its benefits and new uses were found. Hospitals used it keep patients cool, and natural ice-powered refrigeration was becoming central to food longevity, with brewers, meat, fish and vegetable businesses all relying on it. As a consumer, you could pay a subscription to have a weekly ice delivery to your home. In Boston this cost about $2 per month – or $50 per month in today’s money – similar to the cost of home broadband now.

Indeed, ice harvesting helped revolutionize the way we commercially transport and preserve food. Previously, transporting food long distances had to be done in winter, relied on preservation methods like curing (salting) or smoking, or, in the case of beef, were brought to market by epic, cross-country cattle drives. The expansion in the US railroad system at the same time as the advent of cheap and abundant natural ice led to the development of the refrigerated railcar – and suddenly perishable foods could be transported all over the US railroad at any time of the year.

Texas’s cattle, Georgia’s peaches, and California’s citrus fruit all became national industries thanks in part to natural ice. As refrigerated trains led to refrigerated ships, this also helped US beef become an internationally traded commodity.

Frederic Tudor’s one crazy idea led to the birth of an industry that would lay the groundwork for one of the most far-reaching technological inventions of our time: cold on demand.

The rise of “artificial” ice

The downfall of the harvested ice trade came in part due to its huge economic success. It was of no surprise that “fake” ice was invented when it was – the scientific knowledge at the time around thermodynamics and chemistry of the air, as well as other converging technologies meant that its discovery was likely inevitable. But as for all inventions, timing was vital.

Dr John Gorrie is widely credited for designing the first “artificial” ice machine, patenting his machine in 1851. The main aim of his machine was to cool the rooms of his hospital in Florida, to aid the suffering of his yellow fever and malaria ridden patients. Sadly, he didn’t live to see his invention take-off; at the time, natural ice was still abundant and cheap, and (in another part of this story that may sound familiar) the Boston Ice King was said to have launched a smear campaign in the press against Gorrie and indeed the whole idea of “artificial” ice. The New York Globe labelled Gorrie a “crank” and helped spread the idea that the “artificial” ice was infected with bacteria. When it was found that it was actually the natural ice that had pathogens in it – a consequence of the product being harvested from the polluted industrial waterways - the natural ice industry sued the experts and formed “The Natural Ice Association of America” to protect their interests.

Gorrie ended up spending the final years of his life unsuccessfully trying to secure investment in his invention. Meanwhile, the French inventor Ferdinand Carré who designed a refrigeration machine following similar principles to Gorrie patented his machine in 1864. While he is credited with his own independent invention, there are some historic links between the two.

It took an outside event to really propel the use of “artificial” ice in the mass population.

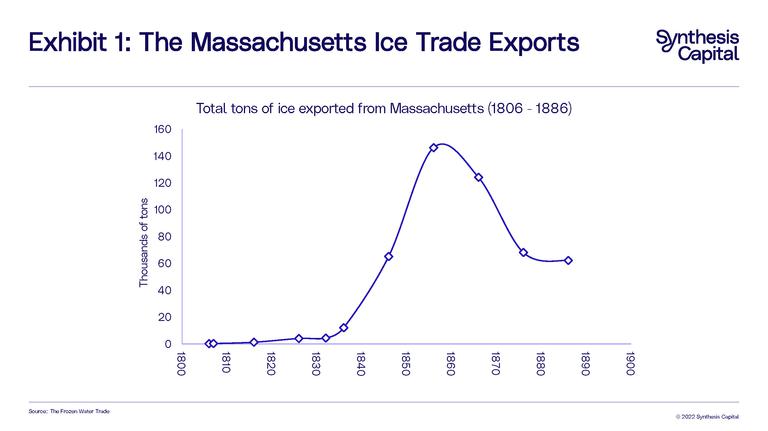

The 1860s marked the peak competitive period in American ice harvesting with the Northern US seeing huge growth (in fact this represented peak exports from Massachusetts –see Exhibit 1). In the South it was a different story. The US Civil war was crippling the ice trade due to the effectiveness of the Union naval blockades. But, like the North, the Southern states had built up an economic and cultural dependence for ice and its benefits. As a result of this, Mr. Bujac of New Orleans smuggled in two Carré “artificial” ice machines from France. These first machines produced just 500 lbs of ice – 250kg, or a quarter of a tonne, per day.

When compared to the amount of natural ice harvested in the north (tens of millions of tonnes), these early machines did not seem viable, as they could not produce the volume of ice the South needed. Yet, as more and more small businesses purchased their own small machines, the strains of depending on the northern ice suppliers diminished and slowly disappeared.

By 1870 the Southern states were making more “artificial” ice than anywhere else in the world. And this marked the beginning of the end for the natural ice trade.

”Artificial” ice takes over

Demand and investment in “artificial” ice grew through the late 1800s – accelerated by supply and demand issues in the incumbent natural ice industry.

First, the supply of “natural” ice became limited due to the formation of ice monopolies and trusts controlling its distribution. This led to increased investment in the “artificial” ice industry by various businesses and entrepreneurs.

In addition, 1880 and 1890 saw two extremely warm winters in the Northern US. In 1880 the ice harvest in the New York area dropped from almost 2.4 millions tons to just 800,000. This showcased how volatile and unreliable natural ice was, and inevitably led to more businesses investing in “artificial” machines.

Indeed, many breweries throughout the United States bought their own “artificial” ice machines – avoiding the supply issues of the natural ice industry and ensuring a constant supply of ice. In 1900, the Anheuser-Busch Brewing Company in St Louis was making almost 1,200 tons of ice per day – making them at the time the largest single manufacturer of ice in the world.

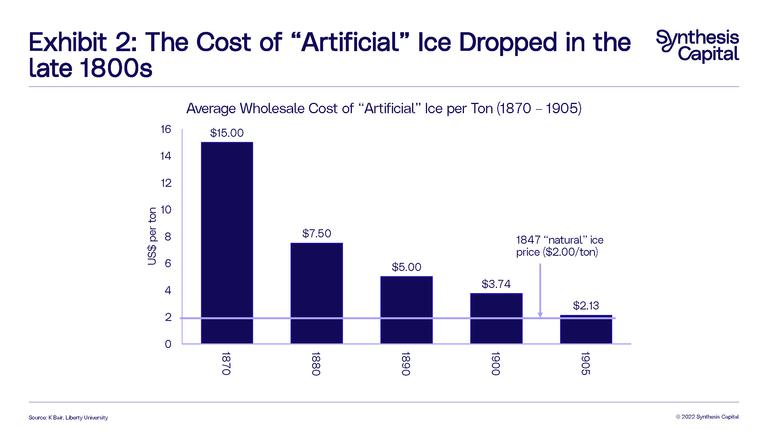

The expansion of “artificial” ice production – along with the process improvements that came along with that – also mean the cost of its production was also falling, and by 1905 was similar to the cost of natural ice production in 1847 – which marked a time it was plentiful and cheap. (Exhibit 2)

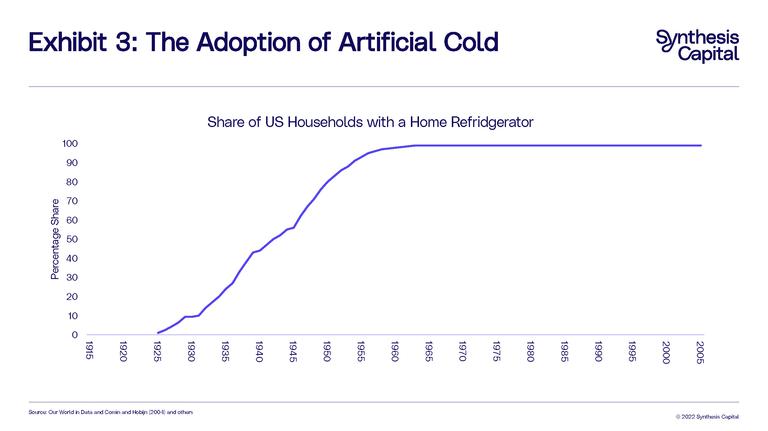

By 1915, the amount of “artificial” ice produced had overtaken that of the “natural” ice industry, but the whole industry was about to change again after the arrival of the first mass produced home electric refrigerator in 1913 – which went on to see S-curve adoption throughout US households and the world (See Exhibit 3).

Cold on demand today

With the introduction of home and local refrigeration, the need for blocks of ice (naturally or artificially produced) waned. Today, most of us in developed countries take refrigeration for granted, we use it every day at a small cost.

The technology behind refrigeration has gone on to impact us all as the technology has continued to improve, leading to other disruptive products, like air conditioning and flash freezing, with far reaching implications. Everything from the food we eat, the medicine we can take, where we travel, even our ability when and how to have children, can be traced back to one man’s dream to bring ice-cream to the Caribbean. There is a reason the Smithsonian voted the refrigerator the most important invention in the history of food in 2012.

What parallels are there for alternative proteins?

The disruption of the ice trade happened due to technology and happened through wars and famine. It created whole new industries and possibilities. History is littered with these stories of technology disruption; and while none are the same – they do, in the words of Mark Twain, rhyme with each other.

For the disruption of “harvested” ice by “artificial” ice we think there are a few key takeaways that help to inform our thinking regarding the coming food disruption.

1. Economics are important and costs are critical

It was only after the cost of “artificial” ice finally hit cost parity with natural ice – which happened once “artificial” ice production had already scaled up significantly in the late 1800s – that its production quickly overtook that of natural ice. So, while the benefits of producing “artificial” cold locally were already understood, making sure it is cheaper or at least equal to costs were still vital to adoption growing. This is an important lesson for alternative proteins. Costs have to come down for alternative protein technology to be as disruptive as we believe it can be.

2. Innovation does not stand still

Products continue to get better even past the point of disruption. The electrically powered domestic refrigerator came after the natural ice trade was disrupted, and home refrigerators today look very different to those first ones – and are continuing to change! (See Exhibit 4).

Alternative proteins are also improving as we have seen technological improvements help mimic everything from the bite of a steak to the “bloodiness” of a burger.

3. Scale is vital to costs coming down and therefore adoption

The first “artificial” ice machines smuggled into the US in the 1860s produced just 500lbs a day – which at the time seemed unviable for the market. The Gorrie factory built in the 1890s was producing up to 30,000 lbs or 13 tonnes per day – 60x increase, and by 1900 plants were producing more than a million lbs per day or 500 tonnes – 2000x those first plants. Scale up wasn’t just about building huge plants, but through the fact businesses everywhere bought their own “artificial” cold machines. It was this dual scale-out and scaleup approach that contributed to lower costs for “artificial” ice.

For alternative proteins, it is no longer a question about proof of concept – we know we can make meat and milk without the cow! We are now focused on proof of scale (both up and out). This is not just about building large facilities, but also about investing in enabling technologies which will all help bring the costs down.

The story of the disruption of ice is a reminder that whole industries can be created when they didn’t exist before, but costs, innovation and scale remain vital. These are top of our minds as we consider the future alternative protein market.

Sources

The story of the disruption of ice is in no way a new one. Many have written about it before – and I am sure they will again! While I have interpreted the story through the lens of technological convergence and disruption, I have relied on many others to help with the building blocks to tell the story. These sources are listed below. Thank you to all.

The Frozen Water Trade: A True Story. 2004. Gavin Weightman. This book details the story of America's vast natural ice trade which revolutionized the 19th century, and the life of Frederic Tudor.

Creating Cold. An article on the BBC by Steven Johnson based on a chapter of his book “How We Got to Now: Six Innovations that Made the Modern World”. February 2015. Please find the link here.

The Civil War, The Ice Trade, And the Rise of the Ice Machine. August 2020. Kevin Bair, Liberty University. Available here. Mr Bair’s fascinating paper argues the move towards using "artificial" ice machines in the US was triggered by the Union Naval blockade of the American Civil War (1861-1865). In addition, this report gives lots of interesting statistics around the rise of the use of “artificial” ice machines, including prices and costs, investment and in particular, information about the conditions in the Southern hospitals without ice! Thank you to Kevin Bair for sharing this with us.

History of America’s Meat-Processing Industry. August 2020. Stacker. Can be accessed here.

Your Fridge Is the Most Important Invention in the History of Food. September 2012. The Smithsonian. Please find link here.