Synthesis Adoption Series: The Consumer and the S-Curve – How Important is the Consumer?

• Market Update • Opinion

When we talk about the adoption S-curve for alternative proteins, we can't ignore the role of the consumer. After all, adoption is the ultimate measure of consumer acceptance.

However, during the very early stages of adoption (where we are for alternative proteins today), what is the hurdle for consumer adoption? Is it the consumers themselves, or are the products simply not good enough yet to meet the needs of a rational consumer (one driven by taste, cost and convenience as opposed to environmental or social reasons). Therefore, should our energy (and investment) be focused on changing consumers’ preferences or on improving the technologies and products on offer to the consumers?

Moreover, when it comes to food, do we, as consumers, actually have a significant say in determining what we eat? While some of us are fortunate enough to choose from a variety of produce at our local supermarket, the decisions behind what food appears on those shelves or on restaurant menus are often made by others, leaving us as consumers with little insight into the process.

In this blog, we delve into the concept of consumer adoption, examining its relation to technological evolution, and pondering whether consumer choice is a mere illusion.

Consumers don’t adopt innovations at the same time because innovations continue to evolve

The adoption of technologies by consumers has been studied for decades. In 1957 George Beal and Joe Bohlen of Iowa State College, published their paper “The Diffusion Process”[i], to explain how farmers adopted a number of new ideas (including the use of fertilizer, crop protection chemicals, antibiotics, deep freezers, and new materials). Later, Everett Rodgers expanded on this concept in his book "Diffusion of Innovation," applying it to a number of technologies[ii]. The "Technology Adoption Life Cycle" – the adoption S-curve – was born, showing that consumer adoption is not a linear process; different individuals adopt new technologies at varying times, each representing distinct stages on the adoption curve.

Consumers' preferences and behaviours are not static because technology continually evolves and matures. As the technology evolves, so does consumer preference. Therefore, to drive widespread adoption, a focus on enhancing products and making them more affordable becomes imperative.

For alternative proteins, and this is something we talk about a lot at Synthesis, a primary barrier to adoption lies in the need for products to improve in every aspect, including taste, texture, nutrition, and environmental impact.

It's essential to recognise that we are still at the very earliest stages of adoption for the more novel food technologies like cultivated meat, precision fermented proteins, and even plant‑based meat and dairy alternatives. The alternative protein products available today on the market still don’t fully reflect the technological advancements in the pipeline. There's so much potential for innovation, and we are only scratching the surface.

With this is mind, should we shift our perspective about consumer adoption? What if, instead of trying to convert an unwilling consumer by bombarding them with why they should switch to alternative proteins, can we reframe the question to – how can we improve the product so that consumer adoption is inevitable?

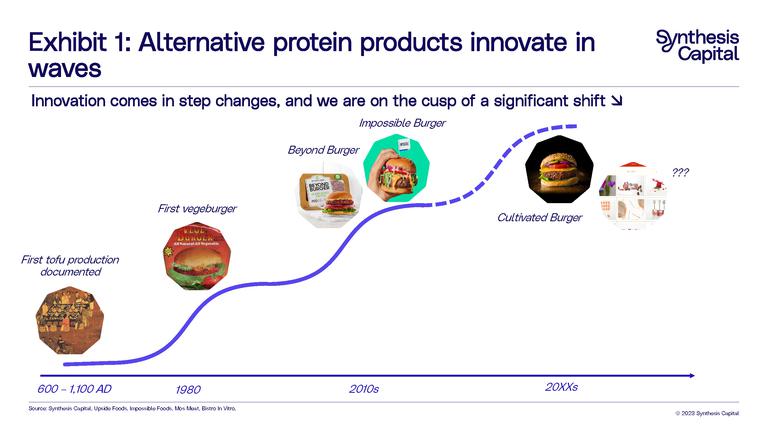

In other words, if we assume that consumer adoption is merely a point-in-time barometer of how good the product currently is, what needs to be done to make alternative proteins too good not to eat? Fortunately, there are many companies in the space working to make products better in terms of taste (optimising protein inputs or using novel technologies like cultivated meat), texture (e.g., 3D printing) and nutrition. We know that innovation comes in waves and we are on the cusp of a significant shift (Exhibit 1).

The illusion of consumer choice

Walking into a supermarket (grocery store!) in the US or UK you are faced with an array of options. From fruits and vegetables sourced from every corner of the globe, irrespective of the season, to an array of meats, poultry, and fish. Displays of bagged, boxed, canned, and cartoned goods, offering a diverse range of cereals, beverages, desserts, and snacks for any palate.

However, our choices are not as diverse as they seem.

Global food markets comprise of long value chains between the farm and fork with a number of significant – and profitable - operators. This value chain is tightly controlled by companies, retail and wholesale outlets, and even governments. The opaque supply chain is particularly evident when we think about processed and manufactured food. For an apple on the supermarket shelves the supply chain is short and fairly transparent (grown on a tree in a field, transported to shop). However, for the third of milk that ends up as an ingredient in everything from chocolate to bread to ready-meals, the amount of steps the products go through, many of which are controlled by oligopolies, is far more opaque.

A number of reports have found that just a handful of giant multinational companies control the majority of market share across each part of the food supply chain. From which supermarket you pick, to the food sold on its shelves, to who has processed the meat and grain ingredients, and even as far which inputs were used to grow the grain, each step is dominated by just a few conglomerates.

Even the choice offered by those supermarket shelves is just an illusion. You may stare at a yoghurt shelf and be overwhelmed by the number of brands, flavours and types of yoghurt available to you. In reality, four companies account for 75% of all yoghurt sales in the US (Exhibit 2).

This oligopolistic pattern is evident across a number of grocery categories. Four companies or fewer control at least 50% of the market for almost 80% of the groceries. And those companies are just one of a handful. In fact in 2018, just nine companies accounted for 60% of all supermarket sales in the US. These percentages don’t necessarily improve either as you go further into the supply chain (Exhibit 2). [iii]

So, as consumers how much choice do we actually have? Are we picking from a pre‑determined set of foods, who are owned by companies with a significantly different motivations?

Consumer Opinions are Constantly Changing

How is this relevant for the alternative protein sector? There are several consumer adoption surveys looking at the willingness of the consumer to purchase and eat a variety of products including cultivated meat, hybrid products, and plant-based alternatives. Most of the time, taste and cost dominate the answers – although of course there are differences between genders, generations, and geographies.

Generally, these surveys have been positive for alternative proteins, with consumers showing a curiosity or willingness to at least try novel food technologies that are still not available at commercial scale. However, they do highlight that the current plant-based meat and dairy alternatives are not up to par, they don’t yet mimic the sensory experience of animal based products, and are not yet cheap enough – something the industry is hyper aware of! Indeed, for some consumers it is the lack of “good” that outweighs the lack of “cheap”.[iv]

It is important to note these surveys represent a snapshot in time. As technology continues to progress, consumer preferences will change as products better meet consumer expectations. Despite this, effort remains focused on changing the perception and attitude of the consumer in order to get them to switch. While we understand that the consumer’s understanding of the technology is very important, today, at Synthesis, we believe it is the scale-up and commercialisation challenges that are more pressing.

Even more importantly, given the above, are these surveys focusing on the wrong consumer? Is it actually the large multi-national food conglomerate producing a plethora of brands and products and deciding the ingredients in each of those actually the key customer?

And if this is true, we may be asking the wrong questions. Should we be focusing on making the products better and more cost effective for those companies that will be using the ingredients in their products? Most importantly, how do we get the companies themselves to embrace these novel technologies? Companies, in some ways are less of a barrier than consumers. First, they are more cost sensitive so that will be key, and the functionality of the novel proteins will also be important – can you just replace conventional animal produced proteins with these novel ones? We also know that companies are directly feeling the pressure from supply chain issues, and from regulation to address climate change. Suddenly, diversifying their inputs in a sustainable fashion is becoming more urgent. The elephant (cow?) in the room is getting bigger.

In which case, is adoption further along that we think? Many of the large food companies have already cited alternative proteins and sourcing as a key strategy[v] in part to meet these sustainability targets – and despite the current news cycle – this isn’t going away.

Conclusion

Whether food-tech innovation is ultimately regarded a success will be measured by its adoption. However, are we focusing too much on the consumer rather than the technologies behind the products at this early stage of adoption? Telling consumers to switch to alternatives proteins because they should for environmental, ethical or health reasons is not working – because the alternative products are not yet meeting the majority of consumers’ expectations on taste, cost and convenience.

This reinforces the need for the industry to focus on improving novel food technologies to meet the basic needs of consumers on these fronts first. At Synthesis we are doing this with our core focus on enabling technologies that will help the industry address regulation, scale-up and commercialisation.

While we in the industry focus on improving and enabling novel food technologies to meet the basic consumer needs on the cost and taste front, perhaps we need to focus on educating consumers better about the technologies that are coming.

The next step is understanding how we get these novel foods to the consumer. Is it the large multi‑national food companies who hold the key? And then once alternative proteins are in every imaginable food on the shelf – will the consumer follow? We think so.

[i] Beal, G. M. and Bohlen, J. M (1957), The Diffusion Process, Agricultural Extension Service Iowa State University. Please find link here.

[ii] Rogers, E. M. (2003) Diffusion of Innovations, 5th edition. Free Press, New York

[iii] Reports include: Kelloway, C. and Miller, S. Food and Power: Addressing Monopolization in America’s Food System from the Open Markets Institute found here. A number of reports from Food and Water Watch around the Economic Cost of Food Monopolies such as: The Grocery Cartels, The Dirty Dairy Racket, and The Hog Bosses. As well as the report Agropoly by Econexus. Articles are written here and here in the Guardian.

[iv] A number of papers and studies have been done around consumer perceptions including: Davide Giacalone, D, Clausen, M.P, Jaeger, S.R; Understanding barriers to consumption of plant-based foods and beverages: insights from sensory and consumer science, Current Opinion in Food Science, Volume 48, 2022. Found here. Also Bryant, C et al; A Survey of Consumer Perceptions of Plant-Based and Clean Meat in the USA, India, and China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 2019 Sec. Sustainable Food Processing. Link here.

[v] The FAIRR investor network (backed by $68 trillion of AUM) released a report in October 2022 showing that “35% of engaged companies have committed to increase the volume or sales of alternatives to meat and/or dairy. This figure is up from 28% in 2021 and 0% in 2019.” The press release can be found here.