Not All Ultra-Processed Foods Are Created Equal

• Opinion

In nutrition science, one framework has gained widespread influence in recent years: the Nova classification system for ultra-processed foods (“UPFs”). Initially developed by Brazilian nutritionist Carlos Monteiro, Nova aims to categorise foods based not on their nutrients, but on their processing.[1]

In this opinion piece, we explore why the Nova classification is just one piece of the puzzle. As we’ll see, not all processed foods are created equal. Thus, we must also consider their nutritional profile, as well as what they’re replacing on our plate.

The study that sparked a movement

The Washington Post described it as “a landmark study providing the most compelling evidence to date that ultra-processed foods are harmful to Americans’ health”.[2] The reason, according to the study? UPFs cause people to overeat and gain weight.

In Kevin Hall’s influential 2019 study, 20 adults were confined to an NIH facility, where they were randomly assigned to either an ultra-processed or unprocessed diet for 2 weeks, followed immediately by the alternate diet for the final 2 weeks. Even though both diets offered the same caloric availability, participants ate roughly 500 fewer calories per day and lost 2 pounds on the unprocessed diet, while they gained 2 pounds on the ultra-processed diet.[3]

Hall’s study elevated Nova’s classification system (more on this below) by promoting the idea that the nature, extent and purpose of processing are a key part of the equation determining healthiness.[4] The evidence, while still limited in number, is becoming difficult to ignore. A growing number of studies suggest that a high consumption of UPFs is associated with a higher risk of several non-communicable diseases (including obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases), and all-cause mortality.[5-7] Global studies like Nilson et al.’s link UPF consumption to premature mortality.[5] That said, there is little—if any—evidence that plant-based meats and other alternative protein products share these negative health outcomes, given they were not included in any of these studies (we explore this distinction in more depth later on).

The growing evidence of the harms of some UPFs (excl. alternative protein products) is concerning, particularly in our convenience-obsessed world, where processed food consumption is rampant. In the US and UK, adolescents consume around two-thirds of their daily calories from UPFs.[8,9] This figure reads less like a statistic, and more like a warning for us to re-examine the food choices we’ve normalised.

In August 2025, the American Heart Association published a number of science advisory highlights. The first reads:

“Most ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) are characterized by poor nutritional quality, contributing to excessive calories, and are typically high in saturated fats, added sugars and sodium (salt), the combination of which is often abbreviated as HFSS, which contribute to adverse cardiometabolic health outcomes, including heart attack, stroke, obesity, inflammation, Type 2 diabetes and vascular complications.”—The American Heart Association.[10]

The Association goes on to state:

“However, not all UPFs are junk foods or have poor nutritional quality; some UPFs have better nutritional value and can be part of an overall healthy dietary pattern.”—The American Heart Association.[10]

Here, the notion of “nutrient-poor UPFs” is introduced. There are, therefore, a limited number of UPFs with more favourable nutrition profiles, “such as certain commercial whole grains, low-fat-low-sugar dairy, and some plant-based items”, which “can be part of an overall healthy dietary pattern”.[10]

This presents a nutritional oxymoron: the seemingly contradictory pairing of a favourable nutritional profile with an ultra-processed classification.

It’s unsurprising, then, that this overlap can create confusion among both health care professionals and the public, prompting questions such as: should I write off all processed foods? What, exactly, makes UPFs harmful? Is it the processing itself, or the fact that these foods are often energy-dense, high in sugar, and low in nutrients?

Let’s take a closer look at this newer approach to nutrition: the Nova system.

What is the Nova system?

“If you can’t make it with equipment and ingredients in your home kitchen, it’s probably ultra-processed.”—Dhruv Khullar, physician and an associate professor at Weill Cornell Medical College.[11]

The Nova system categorises foods into four groups, from minimally processed (e.g. nuts, eggs) to ultra-processed (e.g. frozen pizza, packaged snacks). But unlike standard nutrition frameworks, Nova doesn’t classify foods by nutrients or energy density. Instead, it focuses on industrial ingredients, additives and the degree of processing, often with the implicit assumption that foods made in a factory are less healthy than those made at home. As a result, products as different as protein powder, energy drinks and hot dogs are all grouped together under the broad label of “ultra-processed foods”.

What’s key to remember is this: not all UPFs are created equal.

“There are UPFs with a very good [e.g. protein powder] and with a very poor [e.g. soda] nutritional profile – just as is the case with less processed foods”, explains Dr. Smollich, head of pharmaconutrition at Germany’s Institute of Nutritional Medicine (we added the examples in brackets for clarity).[12]

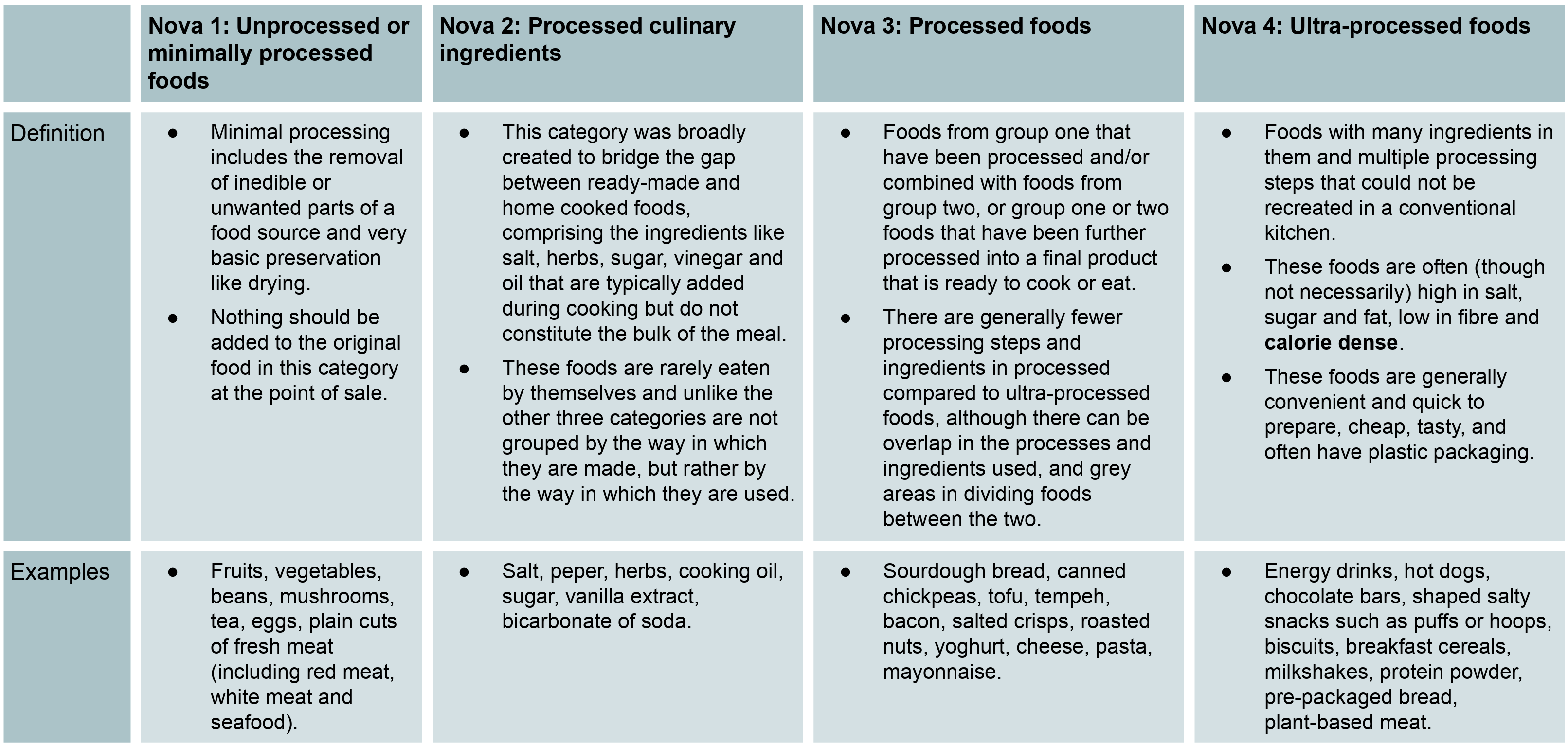

Here’s a breakdown of the four groups and some food examples:

Figure 1: Definitions of food processing using the Nova framework

What does the Nova system mean, in practice?

A pizza made at home with simple ingredients may be classified as minimally processed or processed, depending on the cheese and sauce you use. But that same pizza, if bought frozen, becomes ultra-processed under the Nova system. Add store-bought sausage, and it's definitely a UPF. Unless, of course, you made fresh sausage from scratch in your kitchen.[14] Even routine actions like cleaning, refrigerating or chopping ingredients count as “processing”.[1]

In their podcast episode “Ultra-Processed Foods”, Michael Hobbes and Aubrey Gordon describe the concept of UPFs as “very impressionist”.[15] From a distance, they explain, it makes sense: UPFs appear to be synonymous with what we casually refer to as “junk food”. But look closer, and much like an impressionist painting, the concept starts to become murky and confusing.

A case study in plant-based meats

Few examples expose Nova’s bluntness as clearly as plant-based meats. This is because despite their classification as ultra-processed, recent studies suggest that plant-based meats may be healthier than their animal counterparts, which is completely counterintuitive to the media narrative surrounding them.

Headlines like CNN’s “Plant-based ultraprocessed foods linked to heart disease, early death, study says”[16], along with the popularity of Chris van Tulleken’s bestselling book Ultra-Processed People, have shaped public perception. This is evidenced in the results of a 2024 survey by EIT Food, which found that 54% of European consumers avoid plant-based substitutes because they are ultra-processed.[17]

In response, The Good Food Institute Europe (GFI Europe) and the Physicians Association for Nutrition (PAN International) released a new guide tackling widespread misconceptions about UPFs and exploring the role of plant-based meat in healthier, more sustainable diets.[13]

“This resource aims to equip professionals with a clearer understanding of where plant-based meat fits in—based on science, not sensationalism.”—Roberta Alessandrini, Director of PAN’s Dietary Guidelines Initiative and co-author of the guide.[18]

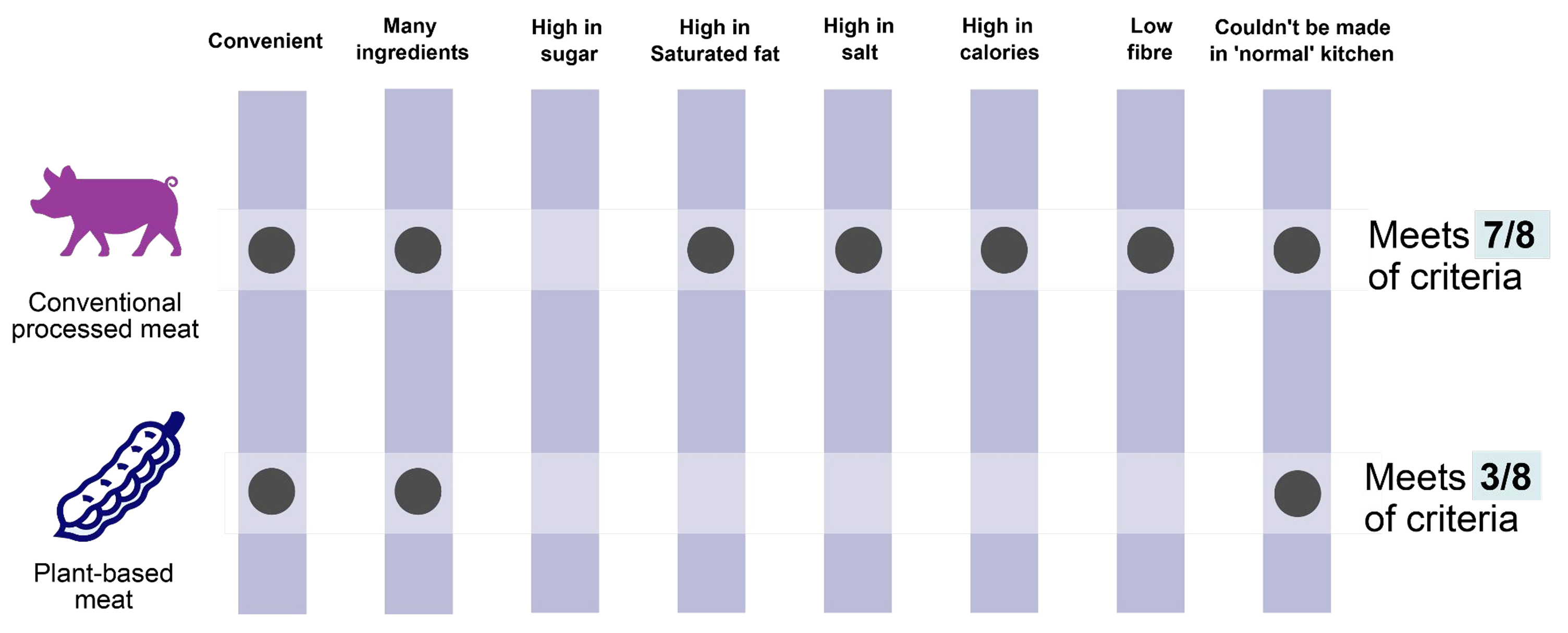

As the image below illustrates, conventional processed meat products (e.g. sausages, curated meats, salamis) are often high in saturated fat, calories and salt, while being low in fibre. By contrast, plant-based meat products are usually a source of fibre, and tend to have lower levels of these common UPF characteristics (e.g. saturated fat, calories, salt).[13] This suggests studies on the UPF group as a whole likely offer little insight into plant-based meat.

Figure 2: Comparison of plant-based meat and conventional processed meat against commonly discussed UPF characteristics

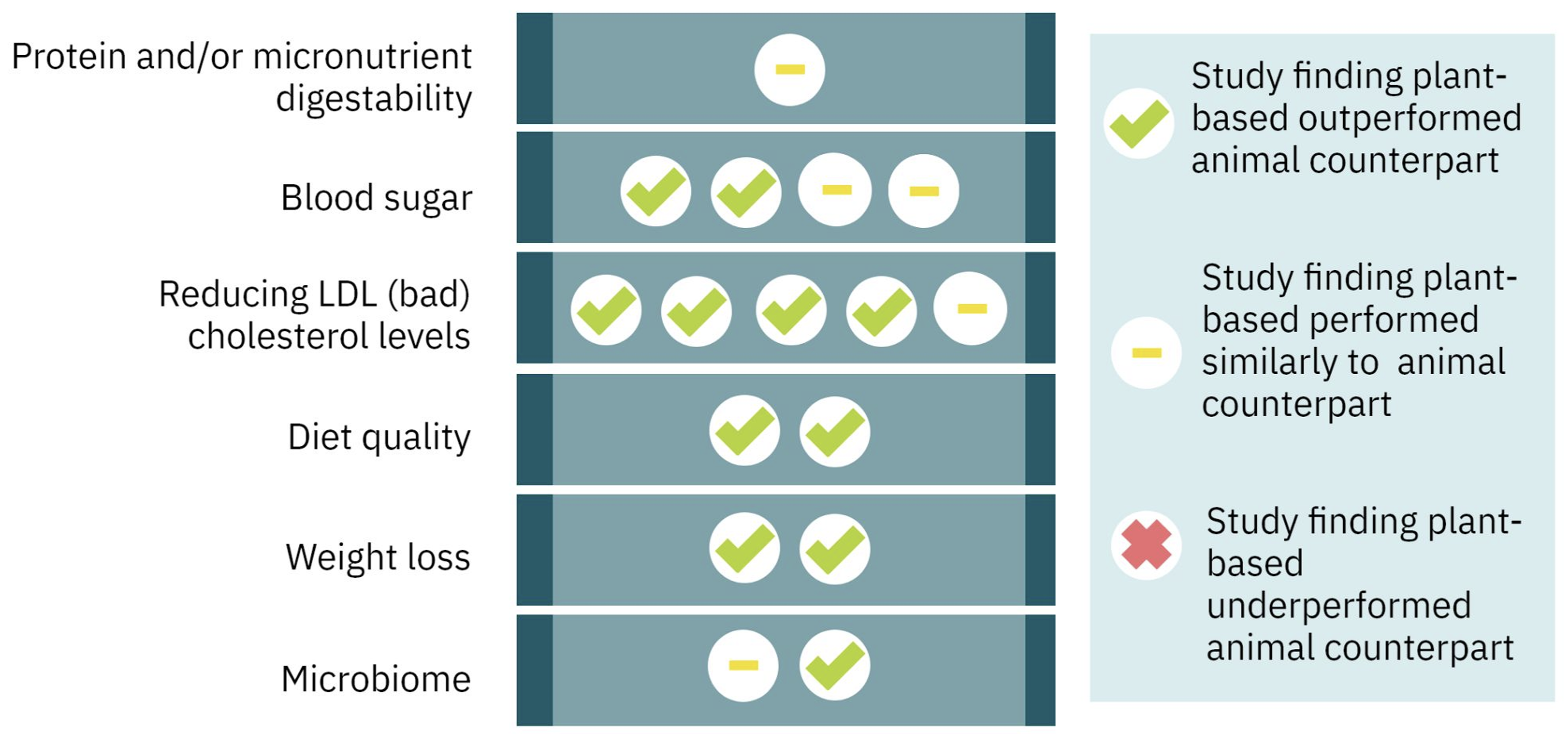

Further, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials found that replacing animal-based foods with plant-based alternatives over an eight-week period led to meaningful reductions in LDL cholesterol and body weight.[19] Similarly, Stanford Medicine’s eight-week SWAP study showed that swapping out red meat for plant-based meat alternatives lowered several cardiovascular disease risk factors, including TMAO.[20] Other studies reported improvements in overall diet quality, microbiome and gut health.[21-23]

Figure 3: Key findings from randomised controlled trials exploring the health impacts of replacing animal meat with plant-based meat

Importantly, these studies don’t claim that plant-based meats are inherently healthy (certainly not more so than wholefood options like a homemade black bean patty). Rather, the evidence shows they’re likely healthier than the animal-based meats they replace. This distinction matters.

What conclusions can we draw from all of this?

-

Not all processed foods are created equal

Lumping cookies and sugary sodas together with protein powders and plant-based meats muddles the UPF category. Instead, we should evaluate each food on its own nutritional merits.

-

We must consider the alternative

When evaluating the health impact of processed foods, it’s important to consider not just how they’re made, but, where relevant, what they’re replacing in our diet. A plant-based sausage may not be perfect (at least not yet), but if it replaces processed meat (classified by the WHO as a Group 1 carcinogenic to humans), it’s likely a healthier choice overall.[24]

To avoid confusion, the WHO defines processed meat as “meat that has been transformed through salting, curing, fermentation, smoking, or other processes to enhance flavour or improve preservation.”[24] This includes products like sausages, ham, corned beef, meat-based preparations and sauces.

-

More processing doesn’t always mean less healthy

In some cases, it’s possible to process foods in a way that makes them more nutritious or digestible. For example, by reducing the amount of fat in dairy products, or by processing plant proteins (e.g. cooking legumes) to improve their digestibility.[25]

Plant-based meats are another category that can be designed to be healthier. For instance, Synthesis portfolio company Redefine Meat recently launched a new plant-based product line with 80% less saturated fat than their previous version, no cholesterol, and more fibre than animal meat.[26] In fact, a new study comparing the nutritional value of 129 meat substitutes from Dutch supermarkets with 54 animal reference products found that the share of healthy meat substitutes (that is, meat substitutes meeting the Dutch Nutrition Centre’s criteria for nutritional quality) has almost tripled since 2023.[27, 28] “The result shows that the market is developing,” says Martine van Haperen, expert in nutrition and health at ProVeg Netherlands.[27]

Additionally, as the American Heart Association reminds us: “Certain types of industrial food processing are beneficial for preservation and safety, and/or lowering cost, such as techniques that extend shelf life, control microbial growth, mitigate chemical toxicants, preserve functional, nutritional and sensory (taste) qualities, and reduce food loss and waste.”[10]

-

More research and clear guidelines are essential

We need to understand what actually is affecting our health. Are UPFs unhealthy because they’re ultra-processed, or because they’re energy-dense and low in nutrients?

The American Heart Association recommends we:

“Increase research funding to explore critical questions about UPFs: To what extent is it the ultraprocessing itself that makes a UPF unhealthy vs. the fact that ultraprocessed foods tend to have unhealthy ingredients?”[10]

In the coming months, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and other agencies, is expected to release the first federal definition of UPFs.[29] Whether it will consider foods’ nutritional profile in addition to its processing remains to be seen.

Closing Thoughts

If we’re serious about understanding how food shapes our health (and we should be), we must consider not just the extent of its processing, but also factor in its macronutrients (like fats, carbs, and proteins), as well as consider what it may be replacing.

Excitingly, alternative protein technology is not static—there’s room for growth and innovation. As we saw with the example of Redefine Meat, who recently launched a new plant-based product line with 80% less saturated fat than their previous version, no cholesterol, and more fibre than animal meat, we’re seeing many companies improve the nutritional profile of their products with formulation optimisations.

As we learn more about which combination of processing methods and ingredients cause the health issues being linked to the currently poorly-defined UPF category, companies will be able to adjust their manufacturing methods to further optimise nutrition while delivering on taste and cost.

Sources

- Monteiro, C. A. 2009. Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing. Public Health Nutrition, 12(5):729–731. Available online.

- The Washington Post. 2025. Prominent ultra‑processed‑food researcher leaves NIH, alleges censorship. Available online.

- Hall, K. D. et al. 2019. Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metabolism, 30(1), 67–77.e3. Available online.

- Petrus, R. R. et al. 2021. The NOVA classification system: A critical perspective in food science. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 116, 603–608. Available online.

- Nilson, Eduardo A.F. et al. 2025. Premature Mortality Attributable to Ultraprocessed Food Consumption in 8 Countries. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 68(6), 1091–1099. Available online.

- Pagliai, G. et al. 2021. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Nutrition, 125(3):308–318. Available online.

- Moradi, S. et al. 2021. Ultra-processed food consumption and adult obesity risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 63(2), 249–260. Available online.

- Wang, L., Martínez Steele, E., Du, M., Pomeranz, J. L., O’Connor, L. E., Herrick, K. A., Luo, H., Zhang, X., & Mozaffarian, D. (2021). Trends in consumption of ultraprocessed foods among US youths aged 2–19 years, 1999–2018. JAMA, 326(6), 519530. Available online.

- University of Cambridge. 2024. Ultra-processed food makes up almost two-thirds of calorie intake of UK adolescents. Available online.

- American Heart Association. 2025. Excessive ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) and poor nutrition tied to poor health. Available online.

- Khullar, D. 2025. Why is the American diet so deadly? Available online.

- Mridul, A. 2025. Scientists Develop Alternative to Nova Classification with ‘Nuanced’ Approach to UPFs. Available online.

- GFI Europe and PAN International. 2025. Where does plant-based meat fit in the UPF conversation? Available online.

- These homemade sausages would fall under NOVA Group 3 (Processed foods) because they are made by combining ground meat (a minimally processed food) with culinary ingredients like salt, spices, and sometimes curing salts to enhance flavour, preservation, and texture. Their preparation involves simple processes such as mixing, refrigerating and baking, without the industrial formulations, additives, or complex processing techniques that define ultra-processed foods (NOVA 4).

- Hobbes, M. and Gordon, A. 2025. Ultra-Processed Foods. Available online.

- LaMotte, S. 2024. Plant-based ultraprocessed foods linked to heart disease, early death, study says. Available online.

- European Institute of Innovation and Technology. 2024. Consumer Perceptions Unwrapped: Ultra-Processed Foods (UPF). Available online.

- PAN International. 2025. New Guide Unpacks the Evidence on Ultra-Processed Foods & Plant-Based Meat. Available online.

- Fernández-Rodríguez, R. et al. 2025. Plant-based meat alternatives and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 121(2), 274–283. Available online.

- Crimarco, Anthony et al. 2021. A randomized crossover trial on the effect of plant-based compared with animal-based meat on trimethylamine-N-oxide and cardiovascular disease risk factors in generally healthy adults: Study With Appetizing Plantfood—Meat Eating Alternative Trial (SWAP-MEAT). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 112, Issue 5, 1188 - 1199. Available online.

- Nájera Espinosa, S. et al. 2024. Mapping the evidence of novel plant-based foods: a systematic review of nutritional, health, and environmental impacts in high-income countries. Nutrition Reviews, 83(7), e1626–e1646. Available online.

- Hartley L. et al. 2016. Dietary fibre for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Issue 1. Art. No.: CD011472. Available online.

- Hooper L. et al. 2020. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Issue 5. Art. No.: CD011737. Available online.

- World Health Organization. 2015. Cancer: Carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. Available online.

- Amanda Gomes Almeida Sá, Yara Maria Franco Moreno & Bruno Augusto Mattar Carciofi. 2019. Food processing for the improvement of plant proteins digestibility. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 60(20), 3367–3386. Available online.

- Mridul, A. 2025. Israeli Startup ‘Redefines’ Plant-Based Meat with 90% Less Saturated Fat. Available online.

- ProVeg International. 2025. Share of healthy meat substitutes tripled in the past two years. Available online.

- In this study, “healthy” is defined according to the Dutch Nutrition Center’s Wheel of Five criteria for ready-to-eat meat substitutes. These include: low salt (≤1.1 g per 100 g), low saturated fat, high protein, and being a source of fibre, iron, and vitamin B12. Products meeting these thresholds are considered healthier choices compared to both other plant-based options and conventional animal meat products.

- Blum, D. 2025. What Makes a Food Ultraprocessed? The FDA Is About to Weigh In. Available online.